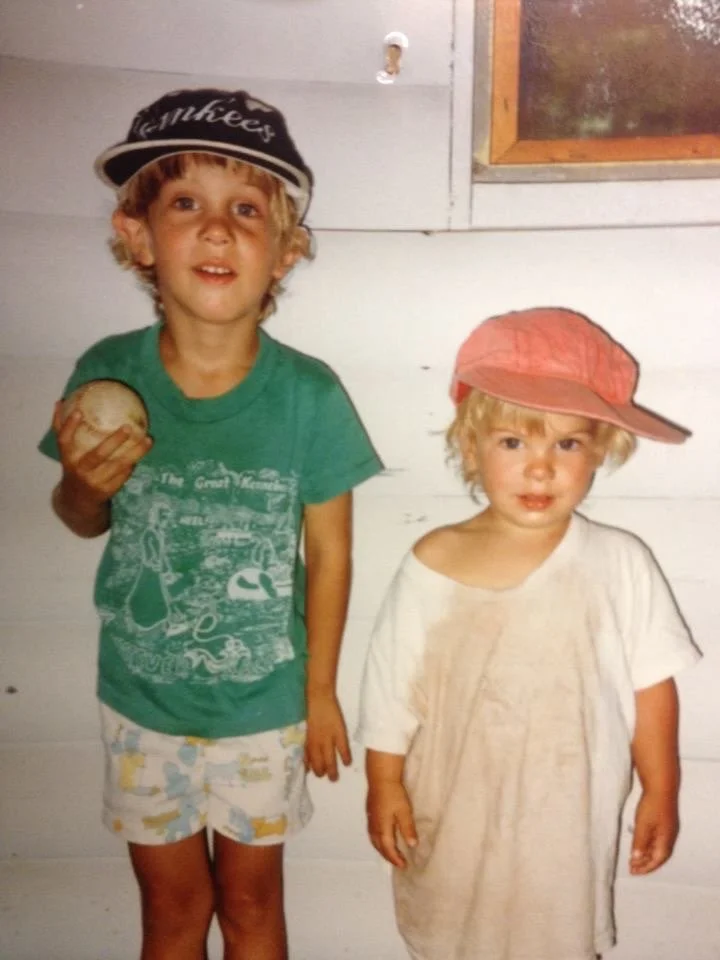

My brother and I in South Gardiner, Maine

About Me

I grew up in rural Maine, where I spent most days in the woods with my brother looking for hidden creatures and treasures—things like snakes, abandoned farm equipment, and old soda bottles. That curiosity eventually led me to archaeology as an undergraduate at the University of Southern Maine. There, with help from my mentors, I discovered zooarchaeology’s unique blend of detective work, evolutionary theory, and cross-cultural thinking.

I now work for the University of Oxford as a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in zooarchaeology.

My ongoing research has taken me all over the world, from Uzbekistan to Zimbabwe, where I’ve been lucky enough to study people who lived over 20,000 years before I was born. By investigating how they related to and interacted with animals, I aim to understand how societies navigated major climatic and cultural transformations over hundreds or thousands of years. The insights I gain allow me to reconsider truths about human existence that aren’t always so obvious in our day-to-day lives.

During my PhD at Washington University in St. Louis (2014-2020), I analyzed over 130,000 bones from a 26,000-year-old rock shelter in Somalia and co-directed pioneering fieldwork along Lake Victoria's shores in Uganda. Alongside this research, I taught courses on topics from climate change to human evolution. Working with students challenged me to communicate complex scientific concepts to diverse audiences—a goal I continue to work toward today.

Since joining Oxford's School of Archaeology in 2021, my research has focused primarily on Great Zimbabwe where I’ve helped develop narratives about the ancient city that emphasize local African ways of seeing and interacting with the world. As part of the ERC-funded New Bantu Mosaics Project, I'm now expanding this work across southern Africa to understand how the spread of farming transformed people and environments over the last 2,000 years.

I am also involved in long-term collaborations at sites in eastern and northern Africa. These ongoing research projects span multiple countries and time periods—from the Pleistocene to the late colonial period. However, all are connected by a single goal: to understand when and why societies and cultures change. I want to know why we aren’t all the same and how this diversity has contributed to humanity’s success as a species. This deep-time approach allows me to consider ongoing issues related to climate change, food security, and biodiversity conservation, particularly how they relate to human flexibility and innovation.

For more information, see my CV.

Excavating at Great Zimbabwe