Research Overview

My work, at a glance

I study how people’s relationships with animals shaped (and were shaped by) social and environmental changes in Africa over the last ~26,000 years. Three broad themes connect my research:

Climate and resilience: How people responded to major environmental transformations.

Mobility and interaction: How the spread of farming and expanding social networks reshaped societies and ecosystems.

Technology and social complexity: How processes of innovation and urbanization informed social resilience and economic sustainability.

Field team, Uganda, 2018

If you want to know more…

Our species has been around for at least 300,000 years. Along the way, we developed many different economic strategies and social systems across wildly different environments, from the Arctic to the Amazon rainforest. Archaeology’s deep time perspective provides a unique opportunity to explore this long history of human variability, revealing societal forms and adaptation strategies that no longer exist today.

My research uses zooarchaeology to investigate the origins of cultural diversity through a fundamental question: How have our relationships with animals influenced societal transformation and resilience? By examining interactions with the non-human world across millennia, I explore the factors that enabled some societies to thrive when faced with environmental and social pressures while others collapsed or transformed completely.

I focus primarily on Africa—the cradle of humanity with the planet's longest archaeological record—using my regional expertise to develop theoretical frameworks that can be applied globally. This Africa-centered approach to world archaeology encourages broad comparative analyses while also challenging Western perspectives on societal development. As a result, insights gained from African contexts provide a basis for rethinking broad assumptions about human diversity, adaptation, and resilience.

My research centers on two interconnected drivers of societal change: environmental transformations and the movement of people, animals, and ideas. Through integrated fieldwork and laboratory analyses, I trace how these two forces shaped human societies from the Last Glacial Maximum through the emergence of complex urban centers.

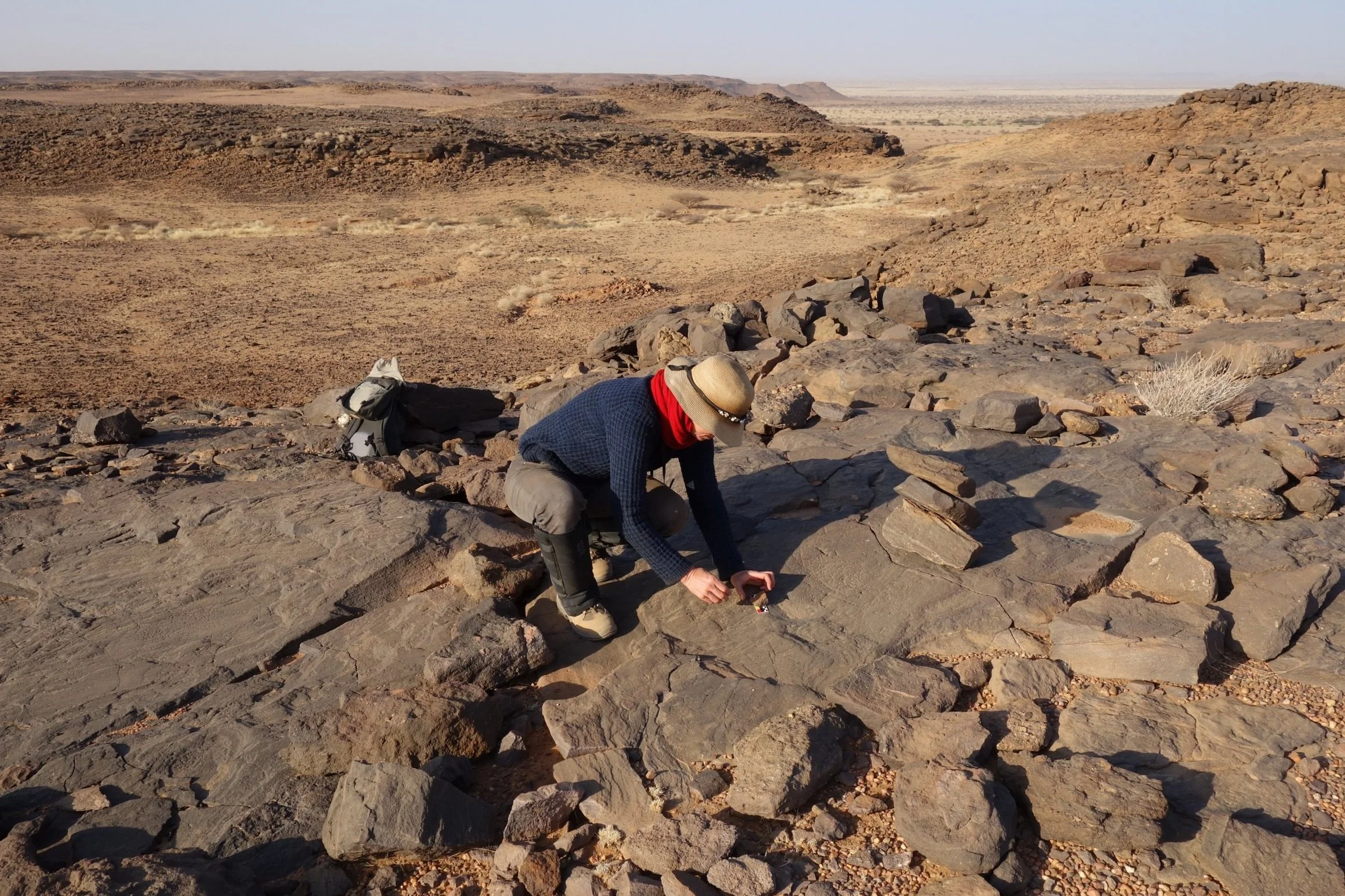

Dr. Varadzinová sourcing lithics in Sudan

Climate Change and Human Responses

Climatic fluctuations have shaped human societies in key ways throughout prehistory, driving innovations in technology, social organization, and resource management. My research focuses on how people in Africa navigated dramatic environmental changes over the last 26,000 years, providing important insights for understanding human ingenuity and flexibility.

Fluctuating rainfall

During the Last Glacial Maximum (~26,000-20,000 years ago), reduced rainfall and expanding deserts forced African populations into refugia around mountains, rivers, and lakes. As monsoon systems shifted north ~13,000 years ago, increased rainfall transformed large swaths of the Sahara into grasslands and forests, enabling Later Stone Age hunter-gatherers to expand into previously uninhabited areas and develop new social and economic systems that involved sedentism and specialized resource management in some areas. Around 6,000 years ago, some groups adopted herding and eventually spread south, introducing domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats to the rest of the continent.

Zooarchaeology and climate change

My research uses zooarchaeological and stable isotopic analyses to reconstruct how different communities adapted their economic and social systems to rainfall fluctuations across three key regions: the Lake Victoria Basin, southern Horn of Africa, and Sudanese Sahel. This work reveals diverse adaptation strategies, from the 20,000-year stability of small-game hunting in Somalia to the dramatic reorganization of fishing communities in Uganda in response to mid-Holocene droughts.

These findings are not just meaningful for archaeology, they also have clear contemporary relevance. Climate projections for northern and eastern Africa are unprecedented historically, making archaeological data an important source for modelling long-term outcomes. By reconstructing large-scale ecological changes and human responses over millennia, my work provides frameworks for understanding how future climate change could affect African landscapes and communities.

Hilltop Enclosure, Great Zimbabwe

Mobility, Interaction, & Transformation

Human mobility and cultural exchange have driven societal transformations throughout prehistory. My research examines how movements of people, animals, and ideas reshaped African societies over the last 2,000 years, with a particular focus on the spread of farming and its impact on local foraging communities.

Bantu-speaking agropastoralists

The spread of Bantu-speaking agropastoralists from western and central Africa represents one of humanity’s most significant migrations. Today, roughly a third of all people living in Africa speak a Bantu language. As these early agriculturalists—the continent's first farmers—expanded east and south, they encountered Indigenous hunter-gatherers and mobile pastoralists, inciting dynamic processes of cultural exchange, adaptation, and innovation. These interactions fundamentally altered economic systems, social organization, and human-animal relationships across eastern and southern Africa.

By the first millennium CE, Bantu-speaking communities had established extensive trade networks connecting inland settlements with polities across the Indian Ocean. Large urban centers like Great Zimbabwe emerged to supply coastal trade with ivory, gold, and other resources, inciting new and sophisticated forms of political and economic organization.

Great Zimbabwe and New Bantu Mosaics

My current research at Great Zimbabwe uses zooarchaeological and isotopic analysis of cattle remains to reconstruct how animal management strategies evolved as political and economic systems became increasingly complex. This work reveals how the choices of individual herders shaped complex economic systems based on cooperation and reciprocity, providing new frameworks for understanding early African urbanism.

Through the ERC-funded New Bantu Mosaics Project, I am expanding this research across 10 southern African countries to trace cultural changes from the arrival and spread of farming through the emergence of cities. By integrating ancient DNA, stable isotopes, and zooarchaeological methods, this work reconstructs how human-animal relationships informed, and were informed by, changing economic and social circumstances.

This research contributes crucial insights into the heritage of Bantu-speaking peoples while revealing how processes of cultural exchange shaped both farming communities and local hunter-gatherer groups. Understanding these deep-time transformations provides frameworks for considering how human movement, interaction, and innovation can drive societal change—which is especially important in our increasingly interconnected world.

For more information, see my CV.